Entertaining Training

Good training is half education and half entertainment. You need to achieve your educational objectives while keeping your members attention and involved. A good instructor can keep this balance throughout each session. Knowing your audience, your subject and your own skills will help you to keep training entertaining.

The first step is to know your audience. If you are the training officer for your department chances are you have been around the department for a few years. Therefore, you should know the gang you are teaching. The problem is that you need to know what they expect to get out of the training and why they attend the training. The mandatory or basic training sessions are the worst because your members are there only because they have to be there.

The goal is to keep the training interesting enough that your members start looking forward to training rather then attending just because they have to be there. One way to do it is to light everything you can find on fire. If there are flames involved or vehicles to rip up then you are guaranteed that the members will find it interesting. Unfortunately this is impractical and would not cover the more mundane training that needs to happen.

If you are looking for mundane training, nothing beats blood borne pathogens or CPR. These are two critical topics that we repeat yearly or bi-yearly and our members would rather pull out their fingernails then attend them. Add that to the AHA’s new CPR video training and it is a load of fun! So how do you keep your members interest and attendance up at these types of classes?

The best answer you can get is to do a bit of thinking about what qualities make a good instructor, what were your best instructors and what qualities make them good? If we can identify the qualities that impressed us about other instructors then we can integrate these qualities into our bag of tricks. Each person learns differently and will appreciate different qualities in instructors, but here is my list: (In no particular order…)

Ability to adapt and be flexible. If you do not have the ability to adapt and be flexible then you should not even continue reading this column. Good instructors have a bit of MacGyver in them and are able to adapt when problems arise. Whenever you need that piece of equipment you can guarantee it will be broken. If you are flexible you will be able to work around the problem. Flexibility also is what allows you to change your teaching style over time and become a better instructor.

Knowledge. An instructor has to have more knowledge then the audience they are teaching. This does not mean that they have to know everything but they should have a higher knowledge level and not be intimidated by the students. There is nothing worse then an instructor trying to bluff their way through an answer to a question just to be proved wrong by a student. You are better off telling the student that you will get back to them with the answer then bluffing your way through it.

Planning. The seven P’s make a good instructor. Proper prior planning prevents piss poor performance. An instructor who does not show up prepared with a plan wastes everyone’s time. When you respect your students’ time then they will respect you and listen to what you have to say. This does not have to be a formal lesson plan but needs to be at least an outline or plan of attack.

Consistency. This is a rather new trait that I have learned to appreciate. I was teaching with one of the instructors that I look up to and realized that he is almost 100% consistent with his training. This means each time he delivers a topic to a new class he delivers exactly the same points, in the same tried and true methods. While this may not work when repeating training to the same people, the consistency goes a long way and shows the amount of planning that goes into each class.

Understanding your audience. Successful instructors gauge their audience often to see what their level is, gain feedback, and understand what is working. You can easily teach above or below your audience. We have a special challenge in the fire service as we have a one room schoolhouse with all levels in our training. Understanding our audience’s needs and expectations will help us when we get to the next step.

Entertaining. Lastly, an instructor should be entertaining. A good instructor needs to keep a good balance in between being entertaining and getting their point across. When you have a strong foundation as an instructor and you can balance the entertainment part, then you can keep CPR interesting.

The ‘color’ in a training session is what keeps members coming. Understanding your audience will help you to determine what type of entertainment is appropriate. What might get a great laugh and drive home a point in one class might offend another class. Sometimes it is as easy as adding in a video clip to spice up the class. Other times you might think about bringing in a special guest.

Personally I like to combine jokes with humorous anecdotes… There is a fine line to walk, but if you can use topical real life examples, your class will appreciate it. The caution is to not go into extended war story diatribes. War stories are good for the club room but you can loose focus easily when too many stories are used. If your anecdote does not directly relate to the topic covered, and cannot be said in under 3-5 minutes, you are best off holding it for the club room.

Next time you sit through a class think about what makes the instructor good (or bad)… Take that information back and integrate it and you will end up with a better class.

The concept of mentoring is not a new idea driven by the business world. Its origins can be traced back thousands of years to a legendary Greek king, Odysseus. King Odysseus left for the Trojan War knowing that he may never return to his young son, Telemachus. In order to make sure that his son was prepared to be a king, he entrusted his development to his close friend, Mentor. Thus began the relationship between mentors and mentees. There is much to be learned from this historical example. In order to develop leaders in the fire service, they must be mentored. Those being mentored must also take part in succession planning as well. They do this by not only being a mentee but by also mentoring the leaders that come after them. Some organizations both in and out of the fire service have recognized the value of mentorship. They acknowledge the importance by creating formal mentoring programs within their ranks. However, most agencies are not this progressive; this requires mentoring to occur on a less formal basis. In order to facilitate this relationship, as either a mentor, mentee or both, certain behaviors will have to be modeled to attract others into the relationship. Mike Nelms' View I would like to quote myself: "Effort and courage are not enough without purpose and direction." Mentoring provides the mentee validation, and inspiration to gather the courage to go for the gold. But this falls short if there isn't a clear intention supporting a vision that provides the purpose and desired direction. A desire or inspiration is always seen as a dream or vision before it becomes reality. A mentor helps the mentee focus on the purpose and gives direction to bring the dream, the need, the goal, into reality. Mentors are my strongest motivators. There are obstructions in my beliefs and flaws in my character I would not have overcome without mentors. Being a mentor provides me with some of my most gratifying experiences. Learning and growing is accelerated. I am self evaluating or reflecting on a more consistent basis. I believe an essential element for success is to be aware of your actions, your intentions, and your outcomes. Mentoring keeps me focused, gives me energy, challenges me, and has helped provide me with the best friends I have in my life today. Looking at some of my desired behaviors of a mentor, for me a mentor must have intentions to: Along with clear intentions, a mentor might take a hint from centuries of success with the ancient Greek philosophy. They knew in order to have the greatest success in the art of influence you must do three things in order: Mentors have a very powerful position of influence on the mentee. It is imperative that the mentor keep focused on the mentee's goals and intentions, and not their own. It is easy to slide down the slippery slope of changing focus from the mentee's needs to the mentor's needs. When the mentee is very engaged, has a high level of trust, goes beyond expectations, has common interests and could very effectively help the mentor meet some of their goals, it is easy to see why some might loose focus. I am not saying that the above should not happen, only that the relationship at that point is changing and should be recognized and agreed to by both mentor and mentee. Great friendships and partnerships can arise from mentorship. Mike Stanley (my co-author) and I have such a relationship. This relationship is the ship that caries us forward. Mike Stanley's View I firmly believe that without the help of others, I would not have enjoyed the many successes that I have had both personally and professionally. Throughout my career, I have been blessed with great mentors. In fact, one of them is my coauthor. Mike, and many others, have assisted me in not only setting goals, but also in achieving them. Without doubt, having a good mentor can be of tremendous benefit. They can help you pursue promotions, college degrees or business ventures. The question is not do I need a mentor, but how do I find one. When searching for a mentor, there are a number of desirable traits that I look for. The traits that I put the most emphasis on are: Closing thoughts http://www.volunteerfd.org/vftraining/articles/445937The Value of Mentoring Programs

Do not judge or allow personal views to skew good advice

Speak your message or better yet, live it; and inspire.

1. Ethos

First build trust. Ethos is your basic ethical nature, credibility, integrity, competency, and the confidence others have in you. Being trustworthy is demonstrated when people consistently come through with their promise and what is expected of them.

2. Pathos

Seek first to understand. Pathos means you have empathy. You have an understanding of their feelings and needs, can see from their perspective, and feel what they are communicating.

3. Logos

Seek to be understood. Your vision, purpose and intentions presented your way provide the power and persuasion of your communication.

Too often being an effective listener is an underutilized skill when it comes to communication. It is important that the mentor listens to my goals, the progress I have made toward them, the obstacles I have encountered and my plan for overcoming the obstacles before they provide input. The mentor is a model but the mentee is not meant to be the exact replica. It is important to know what steps they took to become an engineer or company officer, but it does not mean that I have to do it the exact same way. Also, moving toward goals can be frustrating. Sometimes you just need someone to vent to!

Unfortunately many times it is all too easy to find people in the fire service that have a negative attitude. This is hard to believe, given it is the best profession on earth. It is crucial that your mentor share the same passion for the profession that you do. The people who mentored me to become a lieutenant and then a captain loved leadership. This infatuation with leading others was not only contagious, it was also energizing. By associating with someone who had the proper attitude, it made it that much easier for me to stay positive in spite of the negative individuals I may have came across.

For your mentor to understand the path you are traveling, they must have walked down it before. Whatever you may be working toward, it is best if the mentor has accomplished it before you. That doesn't mean that if they are not a paramedic or have not worked as a volunteer firefighter — and you are — that they should be completely discarded. As we grow and develop, our mentors should meet our evolving needs. There is no rule that says you can only have one mentor. I know that I have many. For instance, when it comes to personnel issues, I know that I can go to Mike because that is an area where he is very experienced. When I was developing a training program for a technical rescue team, his familiarity with this was very limited so I found a mentor that had much more experience in this area.

This may be the most important aspect of all. As a leader in emergency services it is imperative that you possess courage, honesty, integrity, truthfulness, empathy and compassion. If your mentor does not have common values or morals, you will find yourself conflicted throughout the relationship. This really is a deal breaker. The mentor and the mentee do not have to share the same brain, but you must share the same feelings at a visceral level about how you will act as a leader.

We hope that this article enables you to take stock of your own situation. Do you have a mentor? Are you being a mentor? Ask yourself, "Am I demonstrating the qualities that would make me desirable to others as a mentor?" And, "Am I demonstrating the qualities that would make me desirable to others as a mentee? As the industry of firefighting continues to change and the workforce regenerates, make sure that you are prepared to keep up with the growth by turning the theory of mentorship into a reality. See you next month when we will talk about management versus leadership. Be careful out there.

By Carl D. Avery Earlier this year while channel surfing I stumbled across the commencement speech for this year's graduating class from Smith College. It was given by Margaret Edson, a Smith graduate and an award-winning playwright who teaches kindergarten in Atlanta. The focus of her talk was the joys and values of classroom teaching. Her eloquent speech made me think about how we educate our firefighters. Are we training our personnel or are we teaching them? Or is what we are doing a mix of both? And, if it is both, is that the right thing for us to be giving our firefighters? I love the well-tuned bark of a vent saw and tend to buy the most powerful reciprocating saw I can find. Most firefighters have something that is part of their psyche that draws them to the tools of our trade. One thing that often gets forgotten when we buy tools is the human element. No tool or set of tools or piece of apparatus exists in vacuum. True performance comes from how the tools and apparatus interface with their human operators. This includes how well educated that operator is in the mission and capabilities of the piece of equipment they are working on as well as the principles and theories behind it. Teaching versus training The fire rescue business is at once a very simple, yet extremely complex enterprise. On the fire side, it really does pretty much boil down to putting the wet stuff on the red stuff, and on the rescue side, it boils down to making a big enough space to remedy somebody's entrapment. If you are active in our business at all, you know how complex all that simple stuff can get in just a heart-beat. This is why mere training is not enough. Principles of operation You have to recognize what your challenges are. What opportunities does the rescue scenario give you and what are the potentials of your tool? Only after recognizing those factors can you begin to think. Thinking outside the box is where you use non-standard solutions to solve unique challenges. To do this takes more than training. Remember training produces standardized reproducible operations. To think and respond effectively, you need an education that is rich in the hows and whys things work the way they do. One good example of this comes from a rescue instructor from York County, Pa., named Skip Rupert. He has a true understanding of how hydraulic rescue tools work. He realizes that there is more to spreaders than hydraulic fluid opening and closing the tips. He is acutely aware of the geometry of the rescue tool and how that affects the results. When Skip teaches a class he tells his students to think of how the jaws work in an arc and how that impacts what you are spreading. He takes that a step further when he is engaged in hands on training, showing and explaining why the "angle of attack" with your rescue tool can and does make a very real difference in where you are relocating vehicle parts during a rescue. This course of teaching can be very eye-opening to Skip's students, who learn so much more than simply how to make their machine move. His teaching results in a fundamental education that goes beyond mere tool operation. It is an education that delves into maximizing a tool's capabilities and recognizing that the tool and operator interface is critical to achieving the best performance. Structure and discipline Remember this when you buy new equipment. Find out what kind of education and training equipment manufacturers are going to include with the delivery. If they do not offer it, find out where you can get it? And ask why they are not including it? The interface between firefighter/rescuer and machine is truly a matter of life and death. Our lives and our customers' lives depend on us knowing our equipment and getting top performance out of it. The only way to effectively do this is to be taught the principles of our tools' operations and train in evolutions to make the tools deliver all they can. Editor's Note: Carl D. Avery is 37-year member of the Fire Service, originally serving in the Cleveland (N.Y.) Volunteer Fire Department and now the program coordinator at the York County Fire School in Pennsylvania. He is certified as a Fire Instructor II, is a member of the Transportation Emergency Rescue Committee United States of America and is a National Extrication Judge.Tool/Operator Interface Crucial To Performance

Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment Magazine

In her commencement speech, Margaret Edson said, "Showing somebody how to do something exactly the way you've always done it is not teaching, it's training." Achieving standardized repeatable results is not a bad thing in our business. However, we can never get the most out of our fire rescue personnel if our goal is to only achieve "repeatable results."

How many times have you heard the phrase, "think outside the box?" Thinking outside the box takes more than training. It takes being taught the principles and theories of operation and function. Most of what we do, most of the time is pretty straightforward, simple tool exercises for the day-to-day rescue. But every now and then a rescue presents a real challenge. What do we do then? This is where your teaching and training kicks in.

Training is not a bad thing. Training provides the structure and discipline that is needed to make the best use of what you were taught. For success on the street you really need both teaching and training.

By Richard Marinucci Overstating the importance of training may not be possible in the fire service. If fire departments had daily activities reflective of all the responsibilities of the job, then skill levels would be maintained. If the job remained static, then firefighters could get by without training every day. Of course we all know that the dynamic nature of the fire and emergency service requires continual practice and preparation to effectively and efficiently do the job — whatever that may be for the individuals within the organization. Maintaining The Basics Conversely, there are many things that fire departments are asked to do — fire prevention, fire investigation, technical rescue, officer training, and the like — that require added knowledge. There may or may not be the experts in every organization that are truly capable of delivering the training in some or all of these areas. To add to the challenge, often there are few individuals in many departments that require this specialized training at any particular point in time. This can be due to the size of the organization or the size of the prevention, training, or other bureaus of a department. So, what can be done to address this potential deficiency? Consideration should be given to building regional training consortiums to address specialized training within a region. The training can be used to provide information on new and emerging trends, prepare newly assigned personnel and to take advantage of the expertise in many departments. Departments should review the following: None of these can be done in most departments in America due to size and resource limitations. While many states may have programs to help with some of this, like training certifications and arson investigation classes, there are seldom repetitions or refreshers offered which are needed to become and remain competent. Rarely can departments afford to continually train one-person bureaus, nor can they adapt when an individual is away training and not available. Specialty Personnel Start with the simple stuff first. Pooling your funding for specialty training may be the easiest thing to do. Developing resources or utilizing experts in the field can be costly, often exceeding the limitations of many budgets. For example, if you pay $500 dollars to send three of your personnel to training (one per shift, perhaps), you would not be able to afford a full day's training on your own. However, if six departments sent three people, you would not only have 18 in the class, but $3,000 available. You could do a lot more with that amount. Perhaps the class can be offered as a "train-the-trainer" variety. Now each department, and even each shift, has someone available to bring the information back to the organization. A Less Daunting Task Therefore, consider the possibilities if five or six officers are sharing the responsibility. They would be faced with a less daunting task. They also could build upon the individual expertise of each in the group. Clearly you should see some advantages in this approach. If you have resources to do this kind of thing, then why isn't it done? Probably because it is too easy to fall into old habits. It also requires a commitment from the leadership of the organization. The people at the top have to recognize that there is a time commitment up front. They need to understand the investment will pay off later. The leadership needs to encourage all the participants and provide the resources needed. These joint ventures, like so many other "mutual aid" programs are necessary and beneficial. To get started, consider those in your area with like challenges and like philosophies. A small group with similar goals will be more successful than a bigger organization with diverse agendas. Challenging Times In these challenging economic times, organizations need to get creative in their approach to improving service. Training will always be essential to organizations that want to be outstanding. Certainly training can continue on a shoestring budget. But, the next step up will require an investment of time and money. Without adequate resources, an individual organization will struggle. The choice is to join forces with others facing the same challenges and holding the same goals. Like most cases where joint ventures take advantage of individual talents, the outcome will prove way more beneficial than someone going it alone. If departments wish to benchmark against the best, they need to expand their view of the world and look for ways to get the most out of what they have. Editor's Note: Richard Marinucci is chief of the Northville Township (Mich.) Fire Department. He retired as chief of the Farmington Hills (Mich.) Fire Department in 2008, a position he had held since 1984. He is a past president of the International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) and past chairman of the Commission on Chief Fire Officer Designation. In 1999 he served as acting chief operating officer of the U.S. Fire Administration for seven months. He holds three bachelor’s degrees in fire science and administration and has taught extensivelyRegional Training Can Save Time And Money

Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment Magazine

Obviously, much training and practice can take place internal to a department — on a shift, combining stations or scheduled for volunteer and on-call departments. Generally, this training is to maintain the basics and remain proficient in the core skills required. It is as much about practice and repetition as it is about training. Regardless of run volume, all departments must be extremely competent in pulling hose, delivering water, throwing ladders, using SCBA, searching a building and auto extrication, to name some skills, even if these are not everyday occurrences in most departments. This type of training is not especially technical and does not require extraordinary skill or preparation.

• Training and maintaining the skills of fire investigators.

• Training and maintaining the skills of fire inspectors.

• Training and maintaining the skills of public educators.

• Teaching the newest rescue techniques.

• Teaching changes in standards and laws.

• Getting in tune with the hot topics.

• Hearing from nationally recognized experts in the field.

• Preparing officers — from the company level to chief.

• Blending mutual aid responses.

Unless you are a large metropolitan or county department, you probably do not have the resources available in time, money, and expertise to properly train and maintain your specialty personnel. Some of the bigger organizations also struggle with this. If we know this to be the case, then we should work toward a solution. That would be joining with other departments that have the same issues and are faced with the same challenges.

Now, think of the expertise in each department. Most of the smaller organizations have one dedicated person in their training bureau. If that is the case, the individual has way more work to do than time to complete it. The essentials will require most if not all of the time. The training officer will not be able to develop the specialty programs needed.

It is important to gain success early and often. If you do, then others will see the value and want to be part of the program. Your relationship with others will be valuable. Strong relationships build trust and strong programs. While you have a compelling argument to join forces, the interpersonal skills will be most important in getting this venture going.

The Politics of Training

Finding the balance between requiring members to be properly trained and not scaring members away can be very difficult and a common problem for volunteer departments. Chief Tinsley from Tennessee recently e-mailed me with a series of questions from his department that are all too common.

"Training is a big problem in departments from all the time I have been around. The new set of SOG/Handbook that I am putting together has to be approved once finished by the city council. We are a volunteer dept. but are owned by a small city.

The problem that I am having is that I want to require all members to attend a certain amount of trainings in-house per year and also a certain amount of training hours per year. I have some members that are hardcore and will be at every training when the doors open, but on the other hand I have two or three members that never show up for training but will show up on locations for a fire call to help.

I told the city council that all members will have to meet the training and attendance requirements or they would have to be put on the inactive list. These select members that never show up to trainings do have fire training from the past and are certified firefighters. The city council says that with the rules I want to come up with for our handbook such as requiring members to meet certain requirements on training and attendance would be running people away from the dept.

The city council thinks that anyone at anytime should be able to volunteer their services to the dept. I do agree that we can use any and all help whenever we can get it but I believe that if they want to be a member then they should have to obey by the training and attendance rules or not volunteer. So how or what can I use to make this work? I know of the importance of training and that it is a liability and safety measure.

Basically the city council thinks if Joe Blow off the street wants to join the dept., he can and if he can only make one or two trainings a year and show up on occasions at call then that is all that is of importance. But I do not see it that way.

It has to be across the board for everyone so that my butt is covered as well as the city's if by chance one of these members ever screwed up somewhere down the line. So what is one to do when you have members or so-called members that do not want to make the time to train and attend but then also you have the city council say that it is OK for them to only show up just when they want to? Any advice would really be appreciated."

Chief Tinsley's problem definitely represents just one of the many balancing acts that fire chiefs are expected to do daily and deserves to be answered within this column to allow as many folks as possible to learn what can be done."

To address the issue I would suggest a three-step approach:

1. Identify what the state and federal minimum training requirements are for your area.

2. Inform the city council of the minimum requirements and their potential liability if these requirements are not met.

3. Develop a competency-based training system for each of your firefighters to meet or exceed the minimums.

Determining what your state and federal minimum training requirements are can be easy if you know the regulations, or difficult if you need to start from the ground up.

The first question is whether or not your state is an "OSHA state" and if your department has to comply with OSHA regulations. The second would be any requirements from your specific state and your insurance carrier. Fortunately OSHA, and most other regulations, state members must "prove competency" at set intervals rather than "attend training," which will help your department find ways to meet the minimum.

Your city council needs to understand that it is ultimately responsible for the fire service. This responsibility is both to provide fire service to protect the community and to protect the firefighters themselves. Should a member be injured or a fire not handled appropriately, most likely the city will be named in the lawsuit, as will your department and you as Chief. The first thing to occur in any injury or death of a firefighter is to pull the member's file, including training record, which can be a huge issue.

Once you have the minimums in hand and an educated city council, the goal would be to create a program to demonstrate competency at regular intervals of each and every one of your members. This does not mean that each member has to sit through eight hours of training on blood-borne pathogens every year, but they must show competency, an issue which I covered in a previous article.

This does mean your members may have to attend more training or be tested out, but it is for the protection of everyone. Your SOGs or bylaws should clearly state the need to meet these minimums and, given a reasonable amount of time to make up missed training or testing, your members should be pulled off the line until they prove competency.

The three-step plan outlined is not going to be popular with everyone, but it is fair and the bare minimum for safe operations. It is possible you may lose members, but I would much rather lose members than have an injured firefighter due to improper training

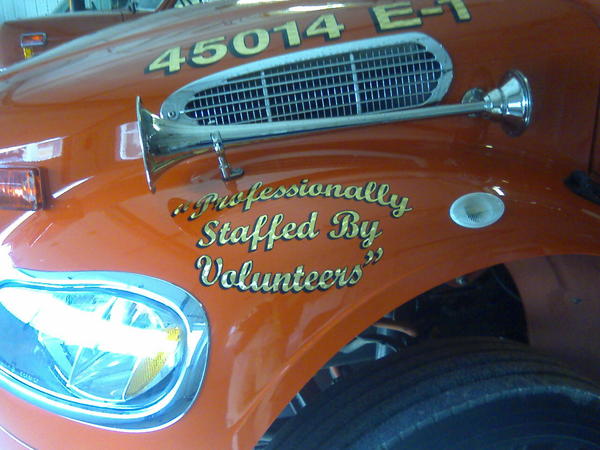

The importance of wiping your feet Customer service is an essential part of every business, yet it is often overlooked in Fire and EMS. Maybe it is because we are the only "safety business" in the town we serve. Maybe it is because our customers cannot chose which department serves them. Maybe it is because we think saving lives is doing "enough" for our customers. No matter why we think it is OK not to provide good customer service, we are wrong. Our public deserves great customer service in addition to saving their lives and property. While we do have a monopoly on providing fire and/or EMS services in our area, that does not mean we can neglect our customers. When the public calls for an emergency, not only do we have to respond, but also we have to treat both the customer and their property with proper respect. Our duty is to mitigate the emergency and save their life and property. If that means wiping our boots before we go in for the CO call to save their white carpets, that is what we need to do. If it means we need to take the time to explain thoroughly to them the risks, that is what we need to do. Departments and their members need to realize that our customers do have a choice. The community we serve also provides our funding and publicity. Negative experiences can mean lasting negative publicity and potential budget shortfalls. Communities have even gone so far as to bring in another department to serve their town because of bad customer service. When your department needs the public's backing for a new truck or LOSAP plan, customer service is what determines if they come out in force to the town meeting. Our customers pick their department by choosing to provide support and funding or not. It is not enough just to save lives. While saving lives is huge, it is actually the way we act while doing it that people remember. There is quite a bit of data in the medical field that demonstrates that when we are nice to our customers they are less likely to take legal action even if there is a negative outcome. Our customers call us at the worst times in their lives and small acts of kindness go a long way towards easing their pain. It is also just the right thing to do. Customer service does not have to be arduous. A small act such as feeding the elderly patient's cat before taking her to the hospital will help her rest soundly. How about taking the time to tarp the hole you just cut in their house? Or maybe just making sure you clean up around the fireplace after you put out the chimney fire. Even more importantly, how about making sure you and all of your members speak appropriately to each and everyone? Just being polite and courteous is at the core of customer service. Providing good customer service may sound like just good common sense, but unless your department makes an effort, it will be overlooked. We are trained to take control, and "do what it takes" to help the public. Unfortunately some members take that just a bit too far. We do not have to break every window in the house just because we can. We also do not need to destroy everything in our path like a bull in a china shop. We are a public service, but we need to remember customer service also. Good customer service is not only the right thing to do but it is what will make our life easier. If your department is truly "Neighbors Helping Neighbors," lets help them in every way we can and make their time of crisis a little bit easier.